A World Repriced

As Washington steps back, debt, de-globalisation, and monetary gravity reassert themselves

If you haven’t yet read it, the US Security Strategy is here.

This maps out a fundamental reordering of US positioning, behaviour, and outlook, recognising that it can no longer act as the global policeman or provide security cover to Europe, which it sees as largely led by weak governments restricting free speech and failing to defend borders. The rest of this bulletin looks at the macro-economic backdrop.

Macro-Economic Backdrop

As we approach year-end, I deal next with the good, the bad, and the ugly to give a balanced assessment of where we stand moving into 2026. This means continued attention to the ongoing tension between extreme monetary policies (aka excessive money printing) and the potential for forces of economic gravity — a tension between two opposing schools of economics, the Austrians and the Keynesians.

The ongoing question we face is whether the next event, whenever it comes along, will be a typical cyclical downturn, caused by recessions that arrive to cleanse excesses (and where the correct response is to ride through to recovery), or whether a structural event unfolds (problems deep in economic engine rooms that require deep fixes).

The latter remains an ongoing risk since the GFC, which was met by extreme money printing and monetary policies. How this tension plays out depends on many factors such as government and central bank policies, the development of dollar alternatives, geopolitics as the world de-globalises into spheres, and the adoption of technologies like blockchain. The truth is we don’t yet know. So far, the global government bond market — including US Treasuries — has been solid, and it enters 2026 in much the same condition, at least at the outset.

Why Gold Is Surging

In 2019, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) quietly designated gold as a Tier 1 reserve asset. This is why central banks globally have been aggressively building gold reserves in preference to US Treasuries.

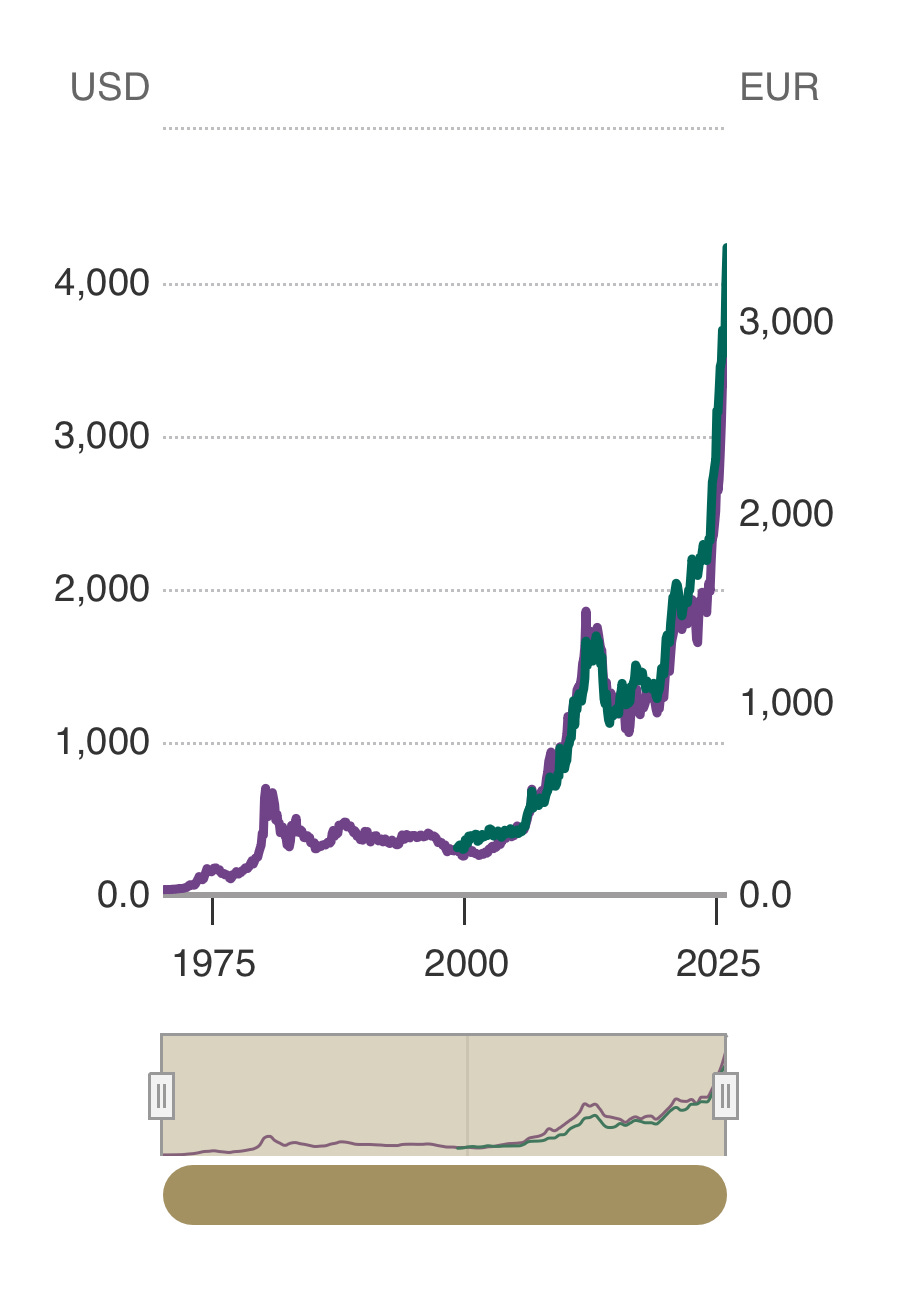

Gold year-to-end (week ending November) is up +46% in euro terms, meaning it has more than doubled in value in just three years. Since its last bear market, all paper currencies have shed more than 90% of their value against gold — the hardest and oldest currency in the world.

Silver, which is much more volatile than gold, has also advanced this year, rising from c.€28 to c.€54 per ounce.

Here’s how gold has behaved since the break from the Gold Standard in the early 1970s, which was followed by over ten years of high inflation before a prolonged bear market in gold to 1999. The dollar is shown in purple, the euro in green. Source: World Gold Council, Washington.

There is a reason for gold’s behaviour over the past 25 years. It relates to the confluence of concerns that we may be approaching the end of a very long-term deficit-financing cycle although there are sharply differing viewpoints on this question.

On one side is the concern that governments have borrowed too much money based purely on confidence in ever-expanding tax receipts from growth. This leads to the conclusion that we are heading for a currency reset, most likely though not yet certainly involving an anchor to gold. This is a viewpoint, not a certainty.

The other viewpoint is that economies can trade their way out and that markets will “melt up” with the Fourth Industrial Revolution upon us. This involves a heady growth cocktail of accelerating and fusing technologies, physical, digital, and biological, with deep systemic impacts across society, jobs, and governance. This is grounded in artificial intelligence, the Internet of Things (billions of connected devices), robotics, automation such as drones, and quantum computing powering processing speeds. The biggest physical constraint is energy, but stacked into that constraint is human innovation: hydrogen, fusion, storage, and more.

What Happens Next?

Firstly, there is nothing we can do to alter the shape of these tensions or future events, other than be aware and position accordingly. This is why I have been adding gold to client portfolios and advocating for it publicly in books, columns, and interviews for 23 years.

No one can accurately predict how long the old deficit-financing cycle can continue. Its demise has been thwarted repeatedly by global central bank interventions using extreme monetary policies. The last coordinated intervention (2020–2021) caused a visible surge in inflation, leading to losses in euro spending power, cash deposits, and many pensions of around -20%. Then came rate hikes, which hurt the government bond market, shaving an average of -15% off values, only now slowly clawing back as rates are cut at a snail’s pace in the USA.

Fed rate cuts are likely to continue into 2026 and 2027, which would ordinarily rally bond markets. Except that markets are now charging higher premiums to nations issuing new debt.

The Year Just Ending

Last week, the US Federal Reserve cut US rates for the third time this year by -0.25%, bringing rates to 3.5%–3.75%. It has been a rapid-paced year, accelerated by Trump’s Liberation Day on April 2nd and followed by his “Big Beautiful Bill”. Meanwhile, Europe whose political landscape is changing fast has committed to large-scale defence and infrastructure spending.

What’s clear is that in the twilight of the year, overall risk levels have settled into a kind of new normal, lower risk than expected in the first half of the year. The peace conference in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict surprised hardened observers and has added to confidence that the US government has regained its footing.

The overarching economic question is whether we are seeing a sustainable revival of the Colossus (USA) under a politically strong US president. The frank answer is that we don’t yet know, this will take time to reveal itself, but we can examine early signs.

Let’s not lose sight of the big macro picture. Global debt levels have reached historic highs, surpassing $300 trillion by mid-2025 (Institute of International Finance data), equating to 3.3x global GDP versus about 2.5x pre-Covid. US debt-to-GDP stands at 123%, Japan at 252%, and Italy at 140%. This compares to average global national debt-to-GDP of around 70% before the GFC. Studies such as Reinhart-Rogoff show that debt above 90% in advanced economies slows economic growth.

On its current trajectory, US debt would reach 180% by 2050. Clearly unsustainable if confidence in the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency is to be maintained. Governments can change this trajectory, but doing so is politically fraught. Reining in spending and cutting taxes can strengthen economic engine rooms but meets popular resistance, so expect a bumpy ride, particularly in less enterprise-led economies.

The risk of an all-out crash is low, barring contagion from a spectacular event. Mid-sized debt crises across economies are inevitable. For now, attention should focus on the behemoths: the USA, China, and Japan.

The key US 10-year bond yield, a thermometer for the Treasury market, declined from 4.57% at the start of the year to around 4.1% today. That is positive. The journey was not smooth, with yield spikes as markets digested Trump’s tariffs and reassessed appetite for US dollars as a reserve currency. Importantly, the yield decline is not purely about confidence; it also reflects recession risks anticipated for 2026–2027, encouraging flows into defensive assets like US bonds.

Gold, meanwhile, has advanced 64% in US dollar terms this year. Central banks continue to build gold reserves as part of the global de-dollarisation trend, which is unlikely to cool soon.

The year began with the euro-dollar at 1.035, moving to 1.175 as the US currency softened across majors. This may partially reverse next year, typical of post-weak-dollar cycles.

It is too early to say whether Trump’s tariffs are a panacea. They are a major gamble, not only on how the US economy responds, but on global trade reactions. Tariff revenues surged, but at the cost of uncertainty, which dampens business investment, fuels inflationary pressures, and risks rekindling trade wars. Some believe this will settle down; perhaps so, but no prudent investor would bet the house on it.

Europe initially faced 20% tariffs and responded through retaliation, diversification, and negotiation, while also stepping up commitments to the Ukraine-Russia war. The result is likely EU GDP growth nearer 1% rather than the earlier 1.5% forecast for 2025, with consumers showing a willingness to substitute away from US goods.

Despite policy shocks, equity markets performed strongly, though concerns about an AI bubble persist. The Euro Stoxx 50 is up 21%, ahead of the S&P 500 at 17.3%, with the UK at 23% and Japan at 26%. These are remarkable figures, reflecting confidence in business performance and AI-driven profit growth as adoption accelerates.

Big Currents

Multi-decadal currents run deep beneath the surface of economics. Because they fall outside short-term timelines, they are often relegated to specialist books or fringe commentary. The classic U-shaped probability models repeatedly fail to reflect the real world’s capacity for extreme events. The modelling that drives most analysis is flawed—that is the point. Quantum computing may eventually help, but for now, accurate prediction remains elusive.

Politicians often assume they can print unlimited currency to fulfil election promises. Unchecked, they exceed sustainable debt-servicing limits, ignore fiscal warnings, and ultimately trigger currency collapse. This is historical pattern, not speculation. Many developed economies are close to or beyond sustainable debt limits. Without course correction, the trajectory ends in crisis, beginning with runaway inflation from renewed money printing.

We don’t yet know the timing, but it appears we are witnessing the decline of the old order of unanchored developed-economy currencies. This partly explains gold’s surge as a superior reserve asset relative to developed-country government bonds, and the view that it will play a leading role in the next currency reset, the last being Bretton Woods after WWII. Gold now exceeds US dollar and euro reserves in central bank holdings.

The key stress point is when rising debt no longer translates into growth because productivity collapses and real wages decline. This feedback loop worsens when government spending is swallowed by debt servicing and welfare, suffocating enterprise. Unless halted by strong leadership, confidence in the currency eventually collapses. Central banks understand this, hence their gold accumulation, and so should we.

This is likely to be a slow, gradual process rather than a cinematic collapse. The US dollar will probably remain the world’s reserve currency for some time, but its dominance will wane, alongside the yen and euro, as we move toward a fusion of gold and digital currencies, the latter acting as decentralised transmission systems.

What to Watch in 2026

Europe

The UK and France sit near the threshold of sustainable debt financing, while Germany struggles with energy affordability for its industrial base. Each requires new national plans and governments with clear mandates.

USA

Watch whether rate cuts fail to correspond with falling bond yields. Weak bond auctions would ripple through mortgages, corporate bonds, collateral markets, and FX.

Japan

For decades, investors have borrowed cheaply in yen to fund higher-yielding assets elsewhere, the “carry trade”. If the US dollar weakens sharply beyond 160–180 JPY, this trade could unwind, prompting large-scale selling of foreign bonds by Japanese investors.

China

Still a conundrum managed through rigid centralisation by the CCP, China sits atop vast unsustainable property debt, up to $11 trillion held by local governments. The CCP’s ambition for 75% urbanisation by 2035 collides with the need to deflate this bubble, echoing Japan’s experience. A major default risks currency crisis and internal unrest, with global spillovers via collapsing commodity prices and a surging US dollar.

What Could Go Wrong?

The base case is a slow puncture before a reset. While views differ on timing and mechanics, all agree financial systems are born, mature, and decline. Nothing lasts forever. The advantage today is foresight and preparation, hence central bank gold accumulation and open debate among banking, commodity, and crypto experts.

Next year, watch the US 10-year yield closely. If it moves counter to expected Fed cuts and surges, it could trigger renewed money printing. So far, the 10-year has weathered Trump’s Rose Garden lunge and stabilised around 4%. That does not yet signal stress in core government debt markets. I suspect bond trouble will emerge elsewhere first, reinforcing US Treasuries and eventually gold as safe havens. We shall see.

Finally, here is a steady, clear-eyed, and moderate Austrian economist, Daniel Lacalle, offering a balanced look into 2026:

I wish you and yours a happy and peaceful New YEar.

Eddie Hobbs